This post was originally published on All Out Cricket on September 14th 2015.

From ‘great white hope’ to ‘fallen idol’ and all reductive points in between, Steven Finn has been pored over, picked apart and ridden out the lot, and he’s still only 26. Phil Walker spoke to the man behind the media narrative about Edgbaston, redemption and the disgraceful things people say.

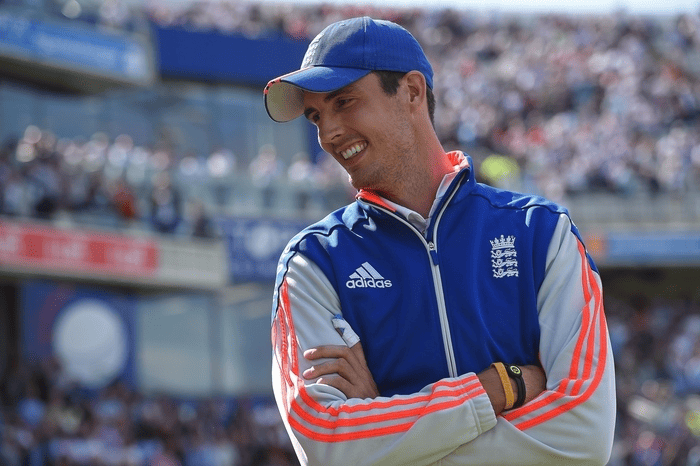

To Edgbaston, with the series at 1-1. Which way it’ll swing, if it’ll swing at all in this weirdest, wildest of rubbers, no one knows. Into this chaos has stepped Steven Finn, 26, recalled to the side. He’s taken 92 wickets from 23 matches up to this point, at a strike-rate around 50, comparable to Johnson, Holding, Garner, Hadlee, and yet it’s two years to the month since his last. The rain’s holding off for now. Michael Clarke wins the toss. He looks down, for he daren’t look up, and dumps England in the Brummie dirt.

Forty minutes in, Finn’s stood at the top of his mark. It’s the last ball of his first over back, the eighth of the match. Australia are already one down. Steve Smith scratches, rearranges himself, settles in again. Having endured four dot balls, the world No.1’s just laced Finn’s fifth through the ring, a shot that cuts through to familiar, disfiguring thoughts: “The first few balls had come out okay,” the bowler recalls, “but then I got hit through the covers and I started to think, ‘Oh Christ, what’s going on here?’”

Steven Finn was once the most promising fast bowler in England. We knew it, the world knew it, and deep down in there – inside this equable string bean from Watford whose knack for bowling fast, nickable balls led to a Test debut at 20 and who would bound to 50 Test wickets younger than any Englishman ever – even he knew it.

He ambled into the team back then much as he did the crease, effacingly, like a hungry young party activist stepping up the garden path for the first time. He never emitted anything much akin to menace, as with Anderson; or scrap-lust, like with Broad. He just ran in and bowled, naturally, often devastatingly, trying to channel his idol McGrath but settling for it coming out like that other big Steve, and that other slave to rhythm: Harmison.

Invariably in those early days, it worked beautifully. In 2010, in his first year around the England team, he began the summer with 9-37 for Middlesex against Worcestershire and followed with 28 wickets across six home Tests. He duly went to Australia as the bairn in the pack and in the first three Tests took 14 wickets, more than any other bowler on either side. Wherever he went, wickets followed. But then, just like that, he was dropped. After a pasting in the heat at Perth left him crumpled in the dressing room, Finn was passed over for Melbourne as England sought solidity, and when they won that match, doing the same at Sydney with Finn again overlooked, his quietly spectacular breakthrough year ended on a mildly bum note.

It seemed just a blip at the time – a sound bit of English safety-first to keep the budding superstar honest. And yet it turned out to be more than that, much more. Between that Perth match in December 2010 and the coin going up at Edgbaston, of the 53 Test matches played by England Steven Finn had appeared in just 12 of them.

The nadir, and there really is no other word for it, came during the last Ashes tour, when a series of “technical deficiencies” left him drained of faith and shot of confidence. I saw him bowl in Alice Springs, in a bizarre two-dayer squeezed in between the Brisbane haunting and the humbling at Adelaide. Finn was already on the outside of things, out of kilter in himself, his run-up a garbled mess having been tinkered with by well-meaning coaches who should have known better. The sight of a 16-year-old wicketkeeper hooking Finn’s soulless drag-downs out of sheer boredom on the final afternoon was just one of the many harrowing tableaus from a hallucinatory tour. He didn’t bowl another ball that winter, eventually being granted honourable discharge midway through the one-day series, and the accompanying noise was deafening: swirling theories, counter-claims, slurs, mistruths, a mute coterie of coaches clinging to tattered methods, an emasculated team, and two sticky words – “unselectable” and “yips” – cruelly plastered onto Finn’s report card.

“It made me livid,” he recalls. “To hear people who are meant to be well-informed in the game, people who have big followings and who have people listening to their opinions, it’s actually harmful when they don’t fully know a situation to be commenting like that. I thought it was a disgrace the way that some people spoke about it and I still wouldn’t have the time of day for those people now.

“It’s all very well sitting there behind your notepad or your computer screen writing things like that but until you actually know the person and know what’s happened, or you understand, you shouldn’t be commenting on things. The little compassion that was shown – some people questioning whether I’d even play cricket again. Yet the day before I left Australia when I supposedly was being fully affected by it, I had a full net. There’s video footage of me bowling in the nets in the moments before I left Australia. There were simply some technical deficiencies in my game that I needed to work on and then I came back, and what’s happened has happened now.”

At Lord’s the week before, Smith had made 215, and that cover-drive is a callback. There’s one ball left in the over. For two years now, Finn says, he’s dreamt only of playing another Test match, of “getting the opportunity” to go again.

“The turning point,” he reckons, “was a game for Middlesex against Somerset at Merchant Taylors’ school.” It was July, and Finn was lively, and alive again, to possibility. He took 4-41 in 20 overs. “I’d been working on an out-swinger for the last couple of years but it was only in the weeks before that match that things started to click and I felt I could control it at good pace. The game against Somerset was the first time I’d stood at the top of my mark and tried to bowl a ball that swings away from the right-hander since I was 16.”

Few cricketers garner as much goodwill as this one, and that spell was briefly the talk of the county game. On the back of it, and a heartening one-day runout in the spring against New Zealand, England, as is their wont these days, merrily threw him into the Ashes squad. Stirred by having reacquainted himself with his untrammelled teenage self – when all he had was himself and his ball, before all the rubbish piled up – Finn jumped all over it.

“In the nets before the match I’d been bowling away-swingers and they were going really well, but it’s almost a comfort blanket to revert back to what you feel you can fully control, with a wobble-ball that doesn’t swing. But when I was at the top of my mark at Edgbaston I just thought, ‘Do you know what? Sod it. What can you do? Back yourself and just roll with it.’ I was literally at the back of my mark and I looked down at the ball and thought, ‘Let’s do it.’ It was almost like telling myself, ‘You’ve got the bottle, do it now, don’t be a pussy.’”

Smith, as he does, leaps across his stumps, setting himself on guard like a court fencer. The raised blade comes down to smother the line but Finn has got the ball to go, first in the air and then, just enough, off the seam. Smith hastily downgrades the punch to a prod but the ball’s left him too late to draw the bat inside and the edge carries to Cook low down at first.

When Finn’s taken wickets for England in the past, he’s generally kept it pretty cool. Not here. “I was just so caught up in making sure that my bowling was right and preparing well, I had no idea what my reaction would be if I got a wicket. At the time he was the No.1 Test player in the world, he’d just made a double hundred, there was a lot of contributing factors behind the release of emotion. I’d dreamt of taking a Test wicket for the last two years. And for it to happen in my first over back, it just overwhelmed me.”

If Smith was a release, the next was confirmation. Soon after, Finn judders one through the defences of the Australian captain to hit the base of all three. “Yeah, it was meant to be full and straight and swinging – thankfully it came out as just about the perfect yorker…”

The innings thereafter fell to Anderson, but Finn would come again with a four-wicket spell in the second innings as pure as fast bowling can be. “I suppose when you talk about being in the zone, you’re doing things without thinking about them. I was running up in that spell and just bowling. I wasn’t thinking about what I was gonna do. It was a weird sensation, going out there and feeling like you’re capable of taking a wicket most balls. It was a surreal experience, something I may not ever experience again in my career.” Eight wickets, and the man of the contest. “Man of the match in an Ashes Test – I s’pose that’s as good as it’s gonna get!”

It’s got fun again. “Our attitude’s been freed up. There’s no fear of going out there and messing up. Rather than being worried about missing lengths and getting hit out the park – it’s now about asking yourself, what can I do to help this situation? Everyone in the squad has that attitude now.”

Steven Finn has gone through quite enough in his England story so far, yet is perhaps only now fully equipped for it. With an exceptional strike-rate and an uppish economy rate, the modern game suits him perfectly. “Yeah, the team I came into five years ago was built on playing attritional cricket and having five-day battles with teams, and whichever team had the patience would come out on top.

“I guess,” he adds, with typical Finnish understatement, “times have changed a little bit…”