This article was originally published on January 11th 2016.

The greatest ever? Possibly. Sir Garry Sobers did things that many cricketers could only dream of, and now he’s able to look back on a fine career from a distance. He went ‘Under The Lid‘ with Jo Harman.

To Bradman, he was “the best cricketer of all time”. For Benaud, “he could do anything… the most complete all-round cricketer I have ever seen”. Setting aside his skill with the ball and in the field, Boycott ranks him as the best batsman he has witnessed.

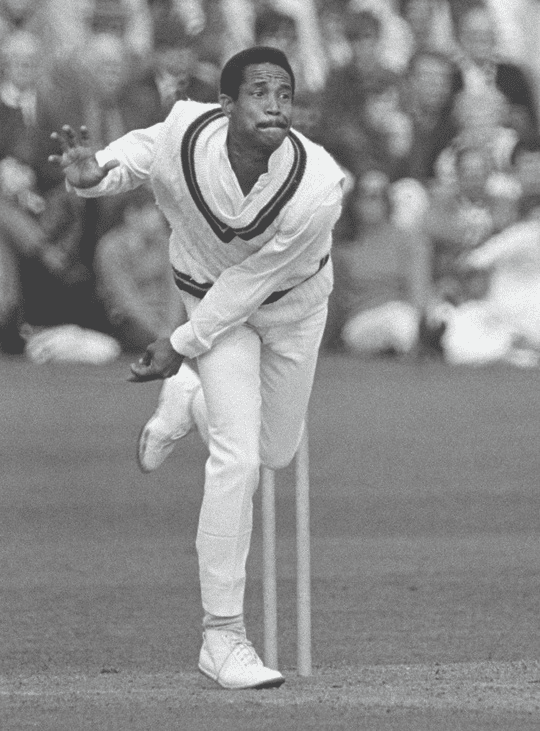

More than 40 years since he played his last Test match, Sir Garfield St Aubrun Sobers is still accepted as the greatest allrounder the game has seen. His statistics are of course exceptional: only eight batsmen in Test history have a superior average; he held the record for the highest score for 36 years; he took more than 1,000 first-class wickets, 235 of those in Tests. But his enduring reputation is based on more than numbers. Look at Jacques Kallis. The South African allrounder averaged only two runs fewer than Sobers, scored 19 more centuries and took 57 more wickets at a better average. Kallis is without doubt a colossus of the modern era but rarely is he described as a genuine rival to Sobers’ title of cricket’s greatest allrounder.

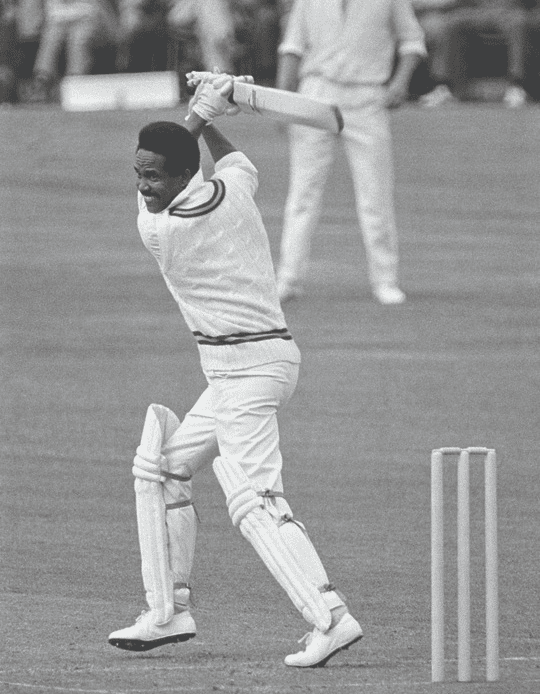

In Bradman’s Best, The Don gives a clue as to why Sobers is rated above all others. “With his long grip of the bat, his high backlift and free swing… Garry Sobers consistently hits the ball harder than anyone I can remember. This helps to make him such an exciting player to watch because the emphasis is on power and aggression rather than technique – the latter being the servant, not the master.”

Bradman goes on to describe Sobers’ innings of 254 for the World XI at the MCG in 1972 as “probably the best ever seen in Australia. The people who saw Sobers have seen one of the historic events of cricket, they were privileged to have such experiences”. Sobers was 35 at the time, his powers supposedly on the wane.

It is these “historic events of cricket” that are at the crux of Sobers’ greatness. Whether it be his Test-record 365 not out against Pakistan as a 22-year-old, his sensational tour of England in 1966 in which he struck three centuries and averaged in excess of 100, his eight-wicket haul at Headingley in the same series, or his six consecutive sixes off a Malcolm Nash over two years later, Sobers repeatedly stretched the game’s boundaries and provoked a reappraisal of what was possible. To do that while maintaining his remarkable statistics marks him out as truly extraordinary.

Sir Garry is now 79 years of age but looks in good nick as AOC meets him at a travel show at London’s ExCel. With silver hair and shades (we’re indoors), he has the air of an ageing filmstar. It feels a bit like meeting a filmstar.

Fittingly, he’s here representing Barbados, as he’s been doing since the age of 16 when he took seven wickets on first-class debut against the touring Indians in 1952. Two years later, he was playing for the West Indies. His passion for West Indian cricket still burns brightly, as was evident at an emotional press conference two weeks before our meeting in which he decried the state of the game in the Caribbean. “I have never made a run for me,” said Sobers, his eyes brimming with tears, voice cracking. “It was such a pleasure and joy to be able to do that. I have always played for the West Indies team. You know, records meant nothing… the team was important. I don’t think we have that kind of person in West Indies cricket anymore. And that hurts.”

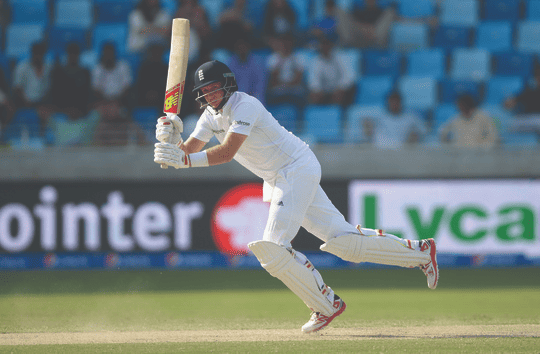

His words were widely reported and today he is reluctant to return to the subject, possibly fearing another media frenzy. Instead, we turn to the subject of greatness. Which contemporary players stand out for him as greats-in-the-making? “There are a number of really, really great players at the present moment. I like your boy here, Joe Root. I think he’s got a lot of class. And I like his attitude because he bats on any type of wicket, he doesn’t pick wickets to bat on. He scores runs, and he scores them fast. And he’s always playing with the bat and always looking to make shots. I like that. He plays for his country and he gets runs in difficult situations. Not going and getting runs when everyone’s getting them – show people you can do it when the chips are down. That’s why I like him.

“England are playing better cricket in this era than they played in past eras because they’re playing a lot more shots. In the older days there were only one or two of them that played shots. There was a lot of pad and bat, pad and bat. I watch English cricket now. I didn’t use to watch it. Because they put bat to ball, and that is wonderful, and they do it well. I admire that.

“Amla of South Africa and the other boy from there, de Villiers. Young Smith from Australia. You’ve still got my boy Cooky going well as an opening batsman. And the two boys from Sri Lanka who have just retired, they were very, very good players. Beautiful players. There are lots of others but those are my specials.”

If you ever happen to have the pleasure of bumping in to Sir Garry, don’t go trying to get him to compare great players from one era to the next. “No comparison,” he says, leaning forward to emphasise the point. “The whole thing has changed and I don’t think you can make comparisons between the past and the present. The bowler is bowling from the front-foot rule, batsmen are wearing helmets, you can only bowl two bouncers an over, they’re playing on covered wickets, you can only have two men behind square. It’s not the same game at all, so it’s very difficult to make comparisons and people keep doing that. You can’t.

“This is a great era, we’ve got great players in this era, but don’t try to make comparisons with people who played on uncovered wickets. If you bowl two balls above the waist these days, not even beamers, then you’re taken off. I remember Freddie Trueman once running in and bowling me a beamer and saying, ‘Sorry old lad, that one slipped’. Next one was quicker! The umpire didn’t send him off! Cricket played in this era is good cricket but too many rules have changed to make a comparison. If there were one or two, I could understand. But there are a million.

“I remember once talking to Imran Khan when they brought in the helmet. I said to him, ‘Imran, why is everyone wearing this mask and this helmet?’ He says, ‘Garry, we’re making money now and we want to be around to spend it’. I said to him, ‘We weren’t making any so we could die?’ That’s the only conclusion I could come to! It’s very difficult to make comparisons and that is not taking anything away from the greatness of the players today.”

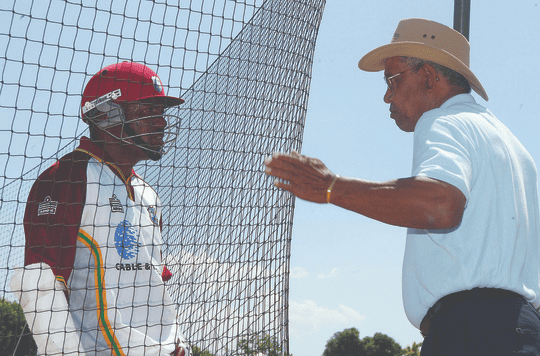

However you choose to measure greatness, Brian Lara qualifies emphatically, and Sobers had a profound influence on the Trinidadian’s career of which he’s immensely proud. The two first met in 1987 at the Sir Garfield Sobers International Schools Tournament – an annual competition in Barbados that is still going strong today – and his face visibly lights up as he recalls their first encounter.

“How could I forget? I remember I was home sitting down when he came. He arrived with a chap called Charlie Davis, who was also a West Indian player, and I lived about 300 yards away from the ground where he was playing. I heard a knocking on the door and there was a little boy out there and he said to me, ‘Are you Sir Sobers?’ – he was a very nervous little boy. He said that Mr Davis had sent him to tell me to have a look at him batting. He was only about 14 or 15 and he couldn’t hit the ball off the square, but you couldn’t get him out.

“The following year he came back. He’d grown bigger and stronger and you could see that he was going to be something very special. I helped him wherever he went. He used to call me and ask, ‘You been watching me, you been watching me?’ – whenever he came to the West Indies, he always asked me to come and coach him. We have kept that relationship through all these years. We are still very close. Brian is like my protégé.

“There was one thing he promised me even at that damn age. He says, ‘I’ll break all your records’. On the day he broke the record [for the highest Test score, at Antigua in 1994] I went into the dressing room and I said, ‘You’ve got a chance, don’t throw it away’. Because records are good things to have but the trouble is if you sit down at home, you want to relax, and as soon as somebody gets to 210, some reporter calls you: ‘Think he’s going to break the record?’ And this happened to me over and over. So I said to Brian, ‘You go ahead, you can handle that’. I’d said that only him or Sachin Tendulkar could break it at that time.

“I knew he was going to do it because Brian is the kind of person that has this mental attitude: ‘Whatever you can do, I can do better.’ And I knew he was going to break that record because I could see it on his face. So I wasn’t surprised when he did it. When a man can make 500 runs… why would you want to make 500 runs! Gee, that’s a lot of energy wasted for nothing! But, you know, he got all the world records in batting. He was really, really a great player, and he is a nice man too. A very nice person.”

Like Lara, Sobers’ career benefitted greatly from honing his skills in English conditions, first in the Lancashire League, where he played for Radcliffe CC from 1958-62, and later with Nottinghamshire, whom he joined in 1968.

Up until 1968 overseas players were required to serve a two-year residential qualification before they could play county cricket but a change to the rules allowed Sobers to become one of several international stars – alongside players such as Barry Richards, Mike Procter and Greg Chappell – to blaze a trail in the shires.

“County cricket was not on my mind because of the situation where you had to qualify for two years,” recalls Sobers. “I would never do that – I would never stop playing Test cricket for two years to qualify. So when they opened the doors, obviously I was going to go in. I had an agent here called Bagenal Harvey – he used to look after Dexter and Compton, he was the big agent – and when I went back to the West Indies I said to him, ‘You look after it, you pick the best county’.

“He picked Notts and it was good because I always enjoyed playing with a team that wasn’t doing well. There’s no sense going to a team that’s doing well, you’ll do nothing. That wasn’t my interest. Going to Notts was a wonderful thing. The only difficult thing was playing against all the other counties at Trent Bridge.

I had to play too many games on much too good a wicket! But it was a lovely wicket, lovely people, I enjoyed every minute playing there and I still go there whenever I come over. That’s one of my great highlights.

“I also enjoyed playing in the Lancashire League when I came back after the 1957 series over here. All of those things helped in my make-up and I think it helped a lot of West Indians because Weekes, Worrell, Walcott, all of us played in the leagues in those days. It helped us tremendously in learning how to play the moving ball and to concentrate, because it’s not like the placid wickets at home where everything comes easy. You had to fight.”

These are different times of course, and it shouldn’t be forgotten that Sobers was paid handsomely during his time in England, but it’s hard to imagine contemporary West Indies players showing such dedication to their craft, taking themselves out of their comfort zone, honing their game in unfamiliar conditions. As Sobers himself says, the eras are incomparable, but that desire to “fight” has been sorely lacking in West Indies cricket for many years now. It’s what brought Sobers to tears in that emotional press conference. One would hope that his words might provide food for thought for the current players and the region’s chaotic, farcical administrators.

Sobers is fearful for the future of Test cricket in general and believes the proliferation of Twenty20 is having an adverse effect. “Twenty20 is entertainment, pure entertainment,” he says. “That’s all it is. And they even bring in the boundaries! Why would you want to bring in the boundaries when you’ve got such great players? How can kids learn? They watch Twenty20 and they believe that sixes is the way to go. There are a lot of cheers, but it’s not cricket. In England, Australia and South Africa, I think Test cricket will remain the utmost for them. Other countries, I don’t know, because the cricket has dropped so far behind.”

He catches himself, the thought of the game’s purest format fading to dust in his homeland perhaps too painful to contemplate. “But West Indies will come again. It will take hard work and dedication, but they’ll come again. Dedication is the important thing.”